Genome editing based on RNA-programmable CRISPR systems enables the modification of specific genomic sequences in living cells, ideally without introducing collateral chromosomal mutations or rearrangements. Nevertheless, despite substantial progress, many critical aspects of DNA editing processes remain incompletely understood and require further investigation and refinement.

In this context, our research focuses on three interconnected lines of investigation:

(i) the development and optimization of viral vectors as delivery agents for CRISPR reagents and donor DNA templates used in homology-directed gene targeting;

(ii) the study of the role and impact of epigenetic processes on the performance of gene-editing tools; and

(iii) the investigation of (epi)genome editing strategies that enable seamless and scarless approaches for the modeling and correction of genetic diseases.

(1) Improving the delivery of CRISPR systems into human cells.

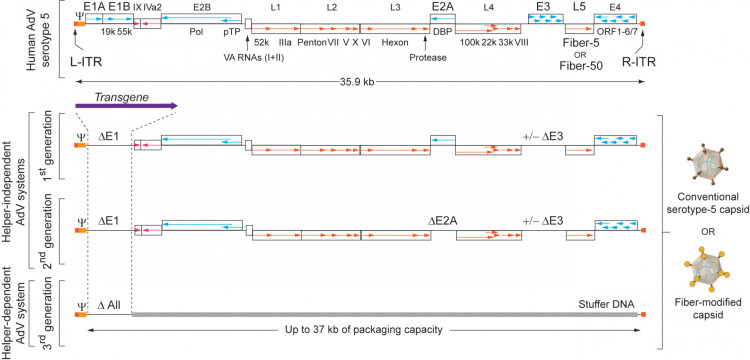

Viral gene-free (high-capacity) adenoviral vector particles (AdVPs) offer several features that make them well suited for genome editing applications, including a large cargo capacity, episomal non-integrating character, high production yields, and efficient transduction of both dividing and non-dividing cells. Our research therefore focuses on assessing conventional and capsid-modified AdVPs as delivery vehicles for genome editing purposes. We develop and test AdVPs with modified tropism to enable efficient delivery into therapeutically relevant human cell types, including striated muscle cells and hematopoietic stem cells (Figure 1). These biological nanoparticles are produced using specialized packaging cell lines designed to minimize the risk of generating replication-competent adenoviruses.

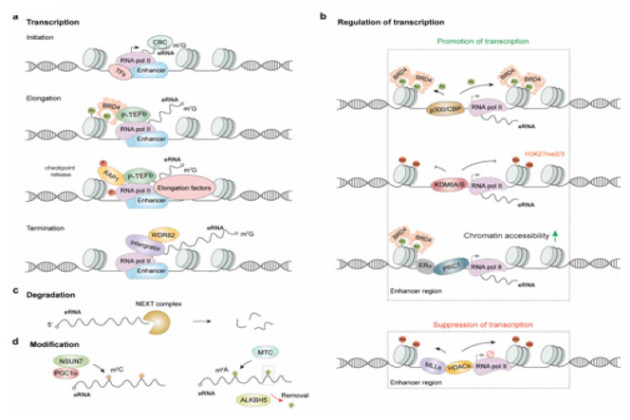

(2) Studying the impact of epigenetic processes on the performance of genome editing tools and strategies.

Once inside the nucleus, genome-editing reagents must act on target DNA sequences that are embedded within complex chromatin structures regulated by epigenetic mechanisms. Because DNA accessibility can vary greatly between open (euchromatin) and closed (heterochromatin) states, understanding how chromatin organization influences the performance of genome-editing tools and strategies is essential. To address this, we have established quantitative cell-based systems in which the chromatin state of identical target sequences can be precisely controlled using small molecules. These reporter systems enable the systematic comparison and selection of genome-editing reagents from different platforms and with distinct designs. In addition, they provide a live-cell readout for assessing editing outcomes, such as the balance between homology-directed repair and end-joining pathways, in relation to chromatin context and donor DNA format.

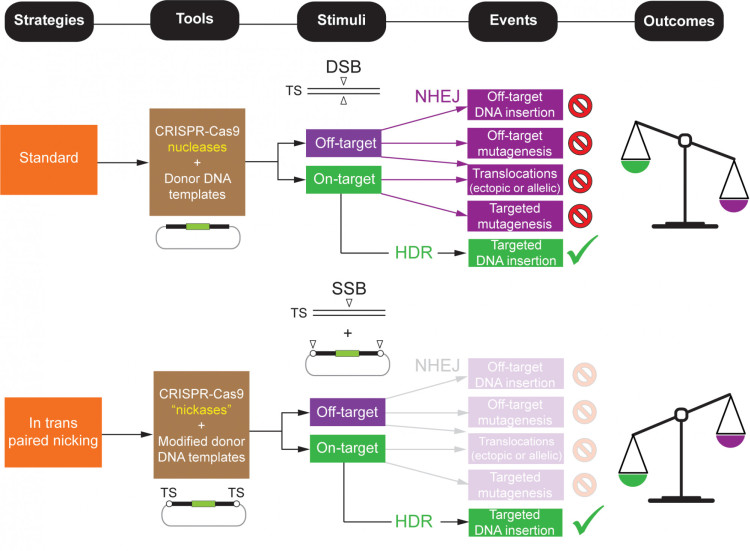

(3) Improving the specificity and accuracy of genome editing procedures.

A major limitation of genome editing based on programmable nuclease-assisted homology-directed gene targeting is that double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) are frequently repaired by the competing and error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) processes. This can result in untoward on-target and off-target mutations, chromosomal rearrangements, and imprecise insertion of exogneous (donor) DNA. To overcome these limitations, we are investigating the use of CRISPR-Cas9 “nickases,” which introduce single-strand DNA breaks rather than DSBs. Unlike DSBs, single-strand breaks are not substrates for NHEJ but can still stimulate HDR, although typically with lower efficiency. Importantly, our work has demonstrated that coordinated nicking of both the target genomic site and the donor DNA template—a strategy known as in trans paired nicking—enables efficient, precise, and non-mutagenic genome editing in human cells, including pluripotent stem cells. We are continuing to explore this approach and to dissect the mechanisms underlying its performance (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Diagram of adenoviral vector systems. L-ITR and R-ITR, “left” and “right” inverted terminal repeats harboring the viral origins of replication; Y, packaging signal. The early (E) and late (L) regions are expressed before and after the onset of viral DNA replication, respectively. First-generation AdVs lack E1A-E1B or E1A-E1B plus E3. Second-generation AdVs have deletions in additional early regions (e.g., E2A and/or E4) being, as a result, produced in their respective complementing cell lines. Third-generation high-capacity AdVs lack all viral DNA sequences except for the non-coding cis-acting elements ITR and Y. Adapted from: Chen and Gonçalves. Engineered viruses as genome editing devices. Mol. Ther. 24, 447-457 (2016).

Figure 2. Comparing standard versus in trans paired nicking genome editing. The relative weights of wanted and unwanted genome editing outcomes resulting from HDR and NHEJ events, respectively, are illustrated. TS, target site; DSB and SSB, double-stranded and single-stranded DNA breaks, respectively; “nickases”, sequence- and strand-specific nucleases. Adapted from: Maggio and Gonçalves. Genome editing at the crossroads of delivery, specificity, and fidelity. Trends Biotechnol. 33, 280-291 (2015).